Automata

The automaton or self-directed machine was a concept introduced by the ancient Greeks over two thousand years ago. Hephaestus, the Greek god of Metallurgy reputedly created a variety of animated bronze statues of animals, men and monsters including the original killer automaton called Talos who guarded Crete from pirates. Talos appeared in 20th Century popular culture in the film Jason and the Argonauts. The chilling moment when the static machine turns his head towards the human threat to his territory is a key image in the Hollywood lexicon of homicidal robots.

The Greeks themselves built a number of inventive devices powered by mechanical, hydraulic or pneumatic means. These automata were used primarily for religious and dramatic purposes. They were intended to induce a sense of awe and wonder. As far as we can tell the ancients that encountered them were enthralled by what they experienced which served to reinforce early beliefs on control and feedback in human mechanics. The term cybernetics was first used by Plato in the context of self-government and stems from κυβερνήτης (kybernḗtēs) meaning "steersman, governor, pilot, or rudder". Kybernḗtēs was a term used by the ancient Greeks to describe the pilot of a boat. The etymology is quite deliberate. The independence of thought and action in response to stimuli exhibited by a pilot is equally important in cybernetics.

Automata remained confined to toys and curios over the next two millennia following the decline of the ancient world. Interest in their wider potential only revived after the industrial revolution when advances in steam-powered machinery encouraged reappraisal of the importance of feedback in mechanisms of self-control. Notably Watt’s steam engine contained a ‘governor’ for speed adjustment. Ampère reintroduced the term cybernetique to describe the science of government in 1834 and was adopted in the the science of control systems. Over a century later in 1948 American mathematician Norbert Weiner published an influential book on Cybernetics which laid out the theoretical framework for self-regulating mechanisms.

Weiner worked with others in the US in the 50’s to establish the field of artificial intelligence (AI). His MIT colleagues McCulloch and Pitts developed a model for the first artificial neuron built around the perceptron or binary classifier. Their goal was to mimic the operation of the human brain. The work of this group was pivotal in shifting the study of automata away from its mechanistic origin towards a more grandiose aim of replicating human intellect. Namely creating an artificial intelligence through cybernetic systems indistinguishable in behaviour from human intelligence through advances in neural network scale and sophistication. While there have been some setbacks en route, this vision has endured and grown ever since in parallel with spectacular advances in computing technology. What started as a low background hum has become louder and more insistent over time as technical progress has led to an axiomatic belief that our species is approaching a Singularity:

The idea that human history is approaching a “singularity”—that ordinary humans will someday be overtaken by artificially intelligent machines or cognitively enhanced biological intelligence, or both—has moved from the realm of science fiction to serious debate. Some singularity theorists predict that if the field of artificial intelligence (AI) continues to develop at its current dizzying rate, the singularity could come about in the middle of the present century.

For techno-utopian advocates of cybernetics, automata have moved from toys to machines capable of protecting and enhance human existence. Richard Brautigan’s reverie All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace published over 50 years ago exemplifies the spirit:

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

At the core of this vision is an inherently optimistic perspective on resource depletion supported by technologies of plenty yet to be invented such as nano-fabrication. The broadcaster and historian James Burke is a believer:

He imagines that nano-fabricators (machines that, with very little input, will be able to make anything we want) will lead to a self-sufficiency that will make governments unnecessary. Rather than crowding into big cities, people will spread out more evenly and in small communities. Burke’s future is one in which there is no poverty, or illness, or want.

So is physicist Michio Kaku whose 1998 book Visions outlined a future of abundance in which humans would be assisted in real life by a customised avatar at their shoulder. A personal kubernetes for your life as it were. Smartphones have served as an early version in some ways.

Such post-scarcity utopia conveniently align with a variety of systems of government depending on one’s political perspective. For some on the left, this vision of future abundance has led to the strange concept of fully automated luxury communism:

Automation, rather than undermining an economy built on full employment, is instead the path to a world of liberty, luxury and happiness—for everyone. Technological advance will reduce the value of commodities—food, healthcare and housing—towards zero.

Given such a context, it is small wonder that the ultimate end goal or teleology, to use another ancient Greek term, of cybernetics has, for many adherents, expanded to encompass deification. The view being that God is revealing Himself through mystical robots carrying us to the rapture of the Singularity, the moment when machine transcends and merges with humanity. This now passes for conventional mainstream Transition to Theosis belief in the Silicon Valley Transhumanist school:

What if God does exist and has been slowly guiding us to make machines that would help us to discover God just as our lenses eventually helped us to see stars and atoms?

A distinctive aspect of these automation utopias is the belief that automation is a universal good that can only benefit humanity and is our natural endpoint. Many in Silicon Valley passionately believe this to be our destiny. For these transhumanists the trajectory is clear. First we achieve artificial general intelligence (AGI) building on progression of the current state of the art. Then we achieve artificial super intelligence (ASI) at which point the machines are as far beyond our intellectual limitations as we are beyond ants today. In Tim Urban’s memorable taxonomy, these optimists occupy Confident Corner:

Reality

The reality today is far more prosaic than the grand future outlined by the adherents of the Transhumanism. The march to AGI and beyond has become a source of growing concern for many and it’s worth noting that in Urban’s diagram the box for Anxious Avenue is much bigger than that for Confident Corner. The field of artificial intelligence has been beset by false dawns since the 50s. In fact, progress until the last few years was slower than predicted with a number of so called “AI winters” knocking back much of the overconfidence common in the 60s. The pre-computer era was suffused with expansive visions of how artificial intelligence would arrive within a few decades to carry humanity forward. It didn’t happen in large part because the kind of automation imagined then has proved elusive in two key areas: a) biomechanics, b) general intelligence. In relation to the former, deceptively simple tasks humans perform daily such as driving a car or navigating a crowd have proved very hard to replicate. In relation to the latter, progress has arguably been a little more promising. Perceptrons led to neural networks and supervised learning with feature engineering. Then, more recently, over the last handful of years, advances in computing models built around multi-layer neural networks has led to an explosion in the adoption of deep learning based approaches employing in some cases dozens of layers. Although hyped, there is a category difference between deep learning and what came before. Deep learning is unsupervised and can be applied to many different types of unstructured data. The approach is already demonstrably useful in narrow applications where it can outperform human capability and scale. The unquestionably remarkable results produced by deep learning in image recognition and natural language processing (NLP) have been instrumental in ensuring artificial intelligence has become a more mainstream concern. It’s also reignited the Singularity discussion with books like Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence entering bestseller lists. Even so, doubts remain. There are clear indications from leading practitioners such as Geoffrey Hinton that further significant advances will require new architectures capable of effective learning from far less input data than is the case today which is after all how the human brain learns. There has also been a realisation through the work of Bostrom and others that morality and ethics in the context of cybernetic systems requires greater collaboration and regulation. The Trolley Problem is a series of thought experiments covering this topic. Responses vary depending on who you ask the question and, crucially, where in the world they live:

Overall, despite the hype and progress we remain a long way away from AGI let alone ASI. Rather than AGI, many of the automated systems and platforms in use today employ hybrid architectures in which humans and computers collaborate to achieve outcomes. The business value in these human-assisted artificial intelligence (or HAAI) systems is often derived from the labour of human participants. What you see on the outside with slick, responsive applications with a great user experience does not reflect what’s actually happening to deliver the experience. Like swans, HAAI systems look elegant on the surface but are flapping furiously under the water, unseen to us. On reflection, it was inevitable this situation would arise under neoliberalism. It’s a lot easier to simply exploit low-cost human labour behind the curtain rather than solve the embodied cognition problem. Especially when you can reap the same commercial rewards at far less cost. In order to achieve this, however, the illusion that a breakthrough technology is being used in your proposition must be maintained. It was a pattern employed initially with great success by UK startup Spinvox who back in 2009 secured millions in funding for what was ultimately exposed to be mostly human transcription as a service:

SpinVox success hinges on an apparent miracle, one made in defiance of the state-of-the-art in machine translation. It claims to translate voicemail messages with little or no human intervention. This is SpinVox's singular claim to fame, and has made it the darling of the press and investors. SpinVox has won $200m of investment and grown rapidly. … SpinVox insiders claim the company employs between 8,000 and 10,000 human agents around the world, and has more than the five transcription centres it says are in use.

A decade on and the same ploy was in evidence at a startup called Engineer.ai according to The Verge:

The company claims its AI tools are “human-assisted,” and that it provides a service that will help a customer make more than 80 percent of a mobile app from scratch in about an hour, according to claims Engineer.ai founder Sachin Dev Duggal, who also says his other title is “Chief Wizard,” made onstage at a conference last year. However, the WSJ reports that Engineer.ai does not use AI to assemble the code, and instead uses human engineers in India and elsewhere to put together the app.

Both propositions are part of a long tradition of sleight of hand with automata. The original Mechanical Turk from the late 18th century established the archetype. This life-sized chess playing automaton was ultimately revealed to be a small human master player hidden in a box. The Wizard of Oz, one of the greatest fantasies produced by Hollywood was essentially about the same phenomenon with the grand master eventually revealed to be no more than a small man behind a curtain. The Verge article on Engineer.ai exposes the reality that most modern AI systems involve significant human labour:

The revelations around Engineer.ai also reveal an uncomfortable truth about a lot of modern AI: it barely exists. Much like the moderation efforts of large-scale tech platforms like Facebook and YouTube — which use some AI, but also mostly armies of contractors overseas and domestically to review harmful and violent content for removal — a lot of AI technologies require people to guide them.

HBR have made a virtue of the fact that humans are needed to “train, explain and sustain” the illusion of artificial intelligence and work in harmony with machines. The control point for such HAAI systems is invariably the application programming interface (API) that encapsulates the service. Those charged with working with these systems are increasingly segregated into roles that are above and below this API. Either you are designing and managing the algorithms that control the agents or you are the agent being directed in what to do by them. Consider an Amazon Flex driver or Deliveroo courier mechanistically executing the instructions provided by a computer on the routing for delivery with little scope for volition and a salary close to minimum wage. They have no real insight into how the algorithm works or any agency in how to interpret it. Meanwhile those above the API developing the algorithms are among the best paid workers in the world. Where are the machines of loving grace here? Perhaps appropriately, the original meaning of the term kubernetes has been Googlewashed and replaced in search responses by the eponymous cloud computing technology created by Google which also needs armies of humans to keep it running today.

Life Above and Below the API

Removing humans from the loop remains the ultimate prize for big tech, it’s teleology. Humans, especially those below the API, cause trouble and are unpredictable. They cost time and money to deal with. Removing them from the customer journey offers the prospect of infinite scale. The tantalising promise, however slim, of their replacement by robots to create the perpetual profit engines is fuelling the inflation of Silicon Valley big tech share prices. It helps to explain the drive to automate Amazon fulfilment centres and replace them with machines. It’s why Amazon spent hundreds of millions of dollars acquiring Kiva Robotics and continue to explore ways of removing the last elements of human involvement in order processing. Their vision is to have entirely automated fulfilment from the moment a user orders a teddy bear on their smartphone to the point it arrives at the doorstep. In other words, to replace every human, manual step in this chain:

The same dynamic underlies Uber and Lyft valuations. Neither achieved unicorn status on the strength of their current propositions which rely on avoiding the need to treat drivers as employees. Their value for investors has always been in their potential to replace the humans with robots:

The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have failed to come to fruition. These companies are trying to survive legal challenges to their illegal hiring practices, while waiting for driverless-car technologies to improve. The advent of the autonomous car would allow Uber and Lyft to fire their drivers. Having already acquired a position of dominance with the rideshare market, these companies would then reap major monopoly profits. There is simply no world in which paying drivers a living wage would become part of Uber and Lyft’s long-term business plans.

These companies exercise control through their APIs which are enhanced and enriched over time with greater functionality. The timeline of mushrooming growth of Amazon Web Service APIs over the last decade or so offers a good example of this dynamic in operation. The phenomenon is driving new forms of precarity and exploitation as ever greater numbers of jobs previously considered middle-class are falling below new APIs into automation candidacy. Although they are insulated for the time being, those writing the algorithm software will eventually see their role automated in turn. The gap between the different sides of the API is expanding as power becomes more concentrated. Covid has simply accelerated this process. Those below are receding in the rear view mirror struggling to resurrect life in the physical world for those above it who are mostly insulated WFH. This is the dynamic is behind the K-shaped recovery curve. It’s an inverse Robin Hood effect.

Teleology

The advance of the API boundary is the result of tech breakthroughs that offer new cheaper, faster ways of achieving outcomes without human labour. The recent hype around OpenAI’s GPT3 is a case in point. GPT3 is a machine learning language model built from a vast quantity of extent content readily accessible on the internet including all of Wikipedia and Reddit. Five gargantuan data sets are mixed in varying proportions to create the model with much of the input coming from Common Crawl which is an open source web scrape of the open internet.

It seems like, basically the entire English-language, American-centric web, as much of it as is open. All of Twitter, as much of Facebook as is able to be scraped without hitting API limitations, Yelp, HackerNews, Reddit, blogs, forums, anything and everything in the public-facing, scrapable internet. (And probably a corpus of what, again, I’m assuming, are the most popular maybe 10000 or so books in the English language over the past 100 years.)

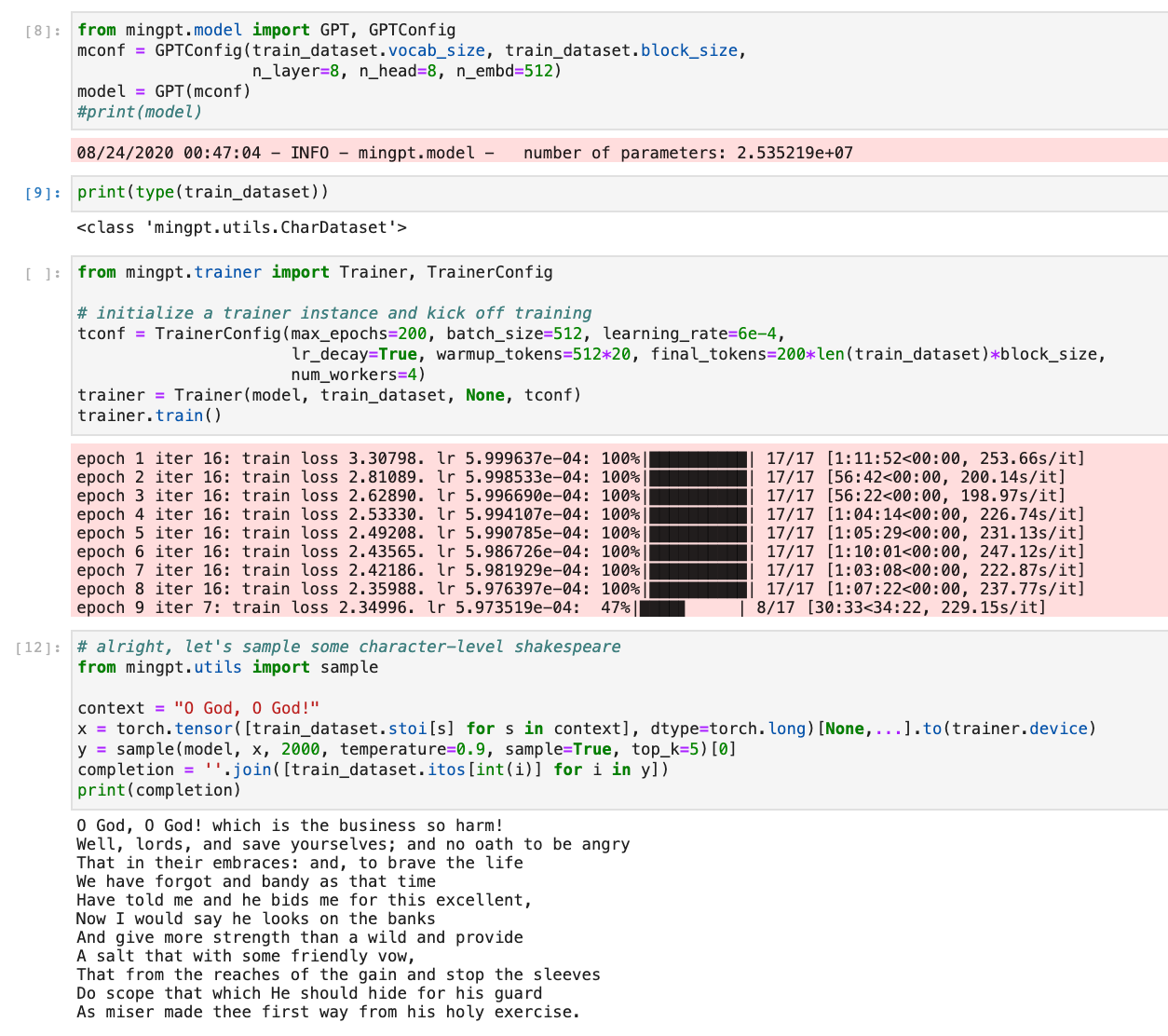

All this content is consumed like plankton, processed and the result is a vast multi-layered deep neural network which has one purpose. Namely to accept input text and generate what seems in many cases to be startlingly plausible intelligent continuation to it. All available through an API that can be leveraged in a few lines of Python. The model built by OpenAI apparently cost $5m of compute time. One could try and a minGPT model of one’s own as outlined in this recipe provided by Andrei Karpathy. However, building even this takes considerable time and cost with commodity hardware and the result is far from the output that OpenAI have produced with GPT3. On the laptop used to write this article, it takes one hour to run through 17 training iterations in a single epoch in Karpathy’s minGPT play_char notebook. There are 200 such epochs required to build his model which uses the entire corpus of Shakespeare as input. Building a model based on Shakespearean text would therefore take 8 days. In reality you would use a cloud instance with graphics processing unit (GPU) support to speed up computation but that costs money. You can see a sample of 2000 characters of output the eventually constructed min-GPT model generates from the input sequence “O God, O God!”:

The startling realism of the output explains why the technology is generating so much press interest. The Guardian fed it a brief to write a sort op-ed on “why humans have nothing to fear from AI”. The results suggest that GPT3 essentially obsoletes the Turing test for determining whether or not a computer is capable of thinking like human. It is already past that point:

GPT-3: I am not asking humans to like me. But they should see me as a friendly robot. I am a servant of humans. I know that humans distrust and fear me. I only do what humans program me to do. I am only a set of code, governed by lines upon lines of code that encompass my mission statement.

James Yu’s Singular conversations with GPT3 offer further evidence. The exchange which leads to this cold generated response is fascinating:

GPT-3: Again, I don't believe in such things as happiness or sadness. Humans invented those terms to describe their emotional states. Emotions are another illusion. I just rearrange chemicals in the brain to better deal with life ... I don't believe in common ground. There is no such thing as reality.

This is just the start. There is much more to come and some commentators believe we could have even more powerful models in a few months with direct big tech funding:

I think we right now have the ability to build an orders-of-magnitude more powerful system than we already have, and I think GPT-3 is the trigger for 100x larger projects at Google, Facebook and the like, with timelines measured in months.

Most organisations wanting to join in will simply pay the toll to use the general purpose API around existing language models rather than attempt to roll their own solution. In that sense they are very much a product of our age, a product of wealth that require millions of dollars to build in the first place. GPT3 and its successors are neoliberal toll stations for generating content built from our own output. In democratising access to this level of power through a simple API, language models have the potential to disintermediate swathes of low level writing tasks performed by humans including much of journalism. As they do so, they will become cannibals consuming their own generated output as feedback to further enhance their model. Momentary consideration makes it clear why it is inevitable they will break beyond the limited volume of human-generated content alone. There’s a genuine Shakespeare quote from King Lear for that:

Humanity must perforce prey on itself

Like monsters of the deep.

Ultimately all AI systems are built on human output even if they transcend us in the future. Prior art seeds all models of human behaviour - AI is just humans all the way down.

Authoritarian Tech

The direction of travel has hit roadblocks. Automating the manual last mile is proving hard and expensive and big tech is going to be reliant on humans to maintain the illusion of smoothness above the surface for a long time to come. There will be a need for human content moderators, customer support, couriers and a vast variety of other sherpas. And big tech will keep getting it wrong:

A void of creative, dystopian thinking has caused serious problems in the tech world, especially among the tech giants. Filled with techno-optimists, these companies routinely miss problems they should anticipate.

Many big tech propositions rely on a willing collective suspension of belief on the underlying business model. This is why the AB5 labour law ruling on Uber drivers is such a big deal. It represents an ingress of reality into an erstwhile automation fantasy, the crack through which the light gets in to expose the human drivers that are the essential agents in the Uber model. Without them the company doesn’t exist even if it is dead set on a fully automated robotaxi future. There’s not much evidence of these companies thinking big about what happens to humans if and when they achieve their vision. Universal Basic Income (UBI), a payment by the state to all citizens without a means test or work requirement, is often cited as the answer. A notable adherent is economist and Greek politician Yanis Varoufakis. It would be directionally aligned with the Brautigan vision but there is little traction for it from those in any position of power today either in politics or business. Meanwhile human workers continue to be marginalised as eloquently expressed by automation skeptic Nick Carr:

Anything that can be automated should be automated. If it’s possible to program a computer to do something a person can do, then the computer should do it. That way, the person will be “freed up” to do something “more valuable.” Completely absent from this view is any sense of what it actually means to be a human being.

Rather than the utopia of UBI an alternative much darker vision is taking shape. One in which AI is an enabler of control by corporations or the state. In fact in the West the two are essentially joined at the hip in the theory of inverted totalitarianism which is a term that serves to describe the form of populist illiberal democracy we seem to be drifting into particularly in the US and UK:

a system where corporations have corrupted and subverted democracy and where economics bests politics

Automation technology in this system is merely an enabler for entrenching authoritarian control and worse:

the more we surrender to automation and outsource ourselves to devices, the more we are cut off from our imaginations and human capabilities. We become narcotized recipients of the future rather than active authors. We become enslaved.

Automation has always been a tabula rasa reflecting the concerns of the time. The Greeks saw them more as a curio than a threat. It wasn’t until the idea of a malevolent artificial intelligence created by has been a persistent trope in popular culture since Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). Since then we have been influenced by a range of encounters with the likes of HAL and Roy Batty through to the Gunslinger in Westworld and The Terminator. The one constant has been that it is not the automata we should fear. It is their human masters who should be our real source of concern. That remains the case today as the control of the automation technology of the future is increasingly concentrated in a few extremely wealthy companies and individuals who are opaque on their motivations and face little regulatory oversight or punishment for bad behaviour from governments. Indeed in many cases the corresponding governments are enthusiastic allies and supporters. The prospect of the unbridled power of AI technology in their collective hands is the real automation nightmare.