The Sixth Extinction

Life Beyond The Event Horizon

The destructive impact of human activity on the environment and life on earth represents an existential challenge for our species. A previous post highlighted the shape of the coming political struggle on how we will respond. On the one hand are the techno-utopians preaching the gospel of Accelerationism who believe that technology can emancipate humanity. Ranged against them are a loose coalition of statists who advocate eco-socialism, degrowth and living within our means. Meanwhile fossil fuel carbon emissions continue unabated with over 50% of carbon produced by burning fossil fuels emitted in just the past three decades. Even if we magically stopped all emissions tomorrow, it would take decades to process what is already in the system. On current trajectory we are due to hit the 1.5ºC rise in as little as 8 years time and the 2ºC threshold shortly afterwards.

Like a doomed traveller drifting inexorably towards a singularity, we already passed our climatological event horizon perhaps as much as 50 years ago largely unaware of what we were doing. That’s the point at which global temperature started its upward hike and the accumulated impact of fossil fuel burning to that point set into motion irreversible changes. Additional emissions since have simply compounded the magnitude of the eventual impact of a phenomenon spread over space and time beyond individual comprehension. Our planet is so vast at a human scale, it is impossible for us to conceive that we live within a vast closed system that we have progressively altered by burning coal, oil and gas. The fact that ecosystems all over the world are under massive stress as a result has only really become an urgent concern over the last few decades. For much of the 20th century humanity was largely unaware we had been running a global scale uncontrolled experiment. That understanding has only emerged in the 21st. Our fate and that of future generations will largely revolve around limiting and accommodating the hyperobject we are enclosed within. We are already seeing the effects of it in the shape of climate refugees from Central America, unprecedented heatwaves, and glaciers melting in the Alps and Greenland. A fuller realisation of the horrors in store for us will only start to emerge in the coming decades and perhaps much sooner than many people realise or expect according to the increasingly alarmed IPCC:

the stark message from the IPCC is that increasingly severe heatwaves, fires, floods and droughts are coming our way with dire impacts for many countries. On top of this are some irreversible changes, often called tipping points, such as where high temperatures and droughts mean parts of the Amazon rainforest can’t persist. These tipping points may then link, like toppling dominoes.

Three recent books offer a brutal, unremitting guide to the terrain. The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells published in 2018 and lauded as “epoch-defining” by The Guardian lands with the ferocity of a carbon-fuelled superhurricane. Its focus is primarily the effects on humanity. The first half of the book is comprised of twelve chapters covering the elements of anthropogenic climate chaos, a nightmare zodiac spanning heat, flood, famine, fires, storms, diseases, wars, sea-level refugees and economic collapse. The second half covers the impact of this chaos on humans in terms of politics, society, economics, ethics and religion. The changes will be so rapid and bewildering that it will be impossible to form a clear single perspective. Instead the ensuing chaos will become a metanarrative, a fractured “climate kaleidoscope” through which everything else will be seen for hundreds perhaps thousands of years hence:

It is worse, much worse, than you think. If your anxiety about global warming is dominated by fears of sea-level rise, you are barely scratching the surface of what terrors are possible—food shortages, refugee emergencies, climate wars and economic devastation.

The Sixth Extinction by American journalist Elizabeth Kolbert which a Pulitzer Prize in 2015 focuses on how human activity has impacted on other species. The book is constructed around thirteen bleak and unremitting chapters each detailing the decline and in some cases extinction of a specific species. Not all were the result of human actions but the ones that were including the Mastodon, the Great Auk and the Neanderthal are unforgettable.

Kolbert’s follow-up Under a White Sky published in 2021 explores how humanity’s future might look in the coming decades as we engage in an increasingly desperate battle to salvage our way of life on earth in the face of climate change. As with Wallace-Wells, for Kolbert that future will not be as imagined in benign mid-20th century futuristic fantasies. It will rather be a world replete with new technologies desperately attempting to fix the damage that previous technologies wrought. She is clear that this will be the defining struggle of the 21st century:

“when we come up against one of these problems we try to come up with the technology to solve it. That is a profound thread in recent human history. How it plays out is perhaps the crucial question in the coming century.” The technology can’t take us back to an undisturbed world. Instead, we are are heading towards a future in which humanity will be constantly reinventing our planet.

The same realisation appears to have been acknowledged by the US Special Envoy on Climate as official US policy prompting scorn from Greta Thunberg:

Kolbert’s two books offer a good framework in which to consider how we got here and what we might have to do to get out. Wallace-Wells contribution is the stuff of nightmares.

The Sixth Extinction

The Sixth Extinction considers human impact on the environment and climate in the context of deep geological time. There have been five previous great extinctions in the last 550 million years. The infographic below provides a helpful summary. It fits the chronology presented in the book which focusses on the twelve Periods spanning the Phanerozoic Eon to the present day. Kolbert provides a helpful mnemonic for remembering these Periods. Extending it to cover the three since the Cretaceous Extinction 65 million years ago that killed off the dinosaurs, we get the following:

Camels Often* Sit Down* Carefully Perhaps* Their* Joints Creak* Perhaps Not ?This construction captures all the Periods from the Cambrian through to the current Quarternary denoted by the question mark. The asterisks provide a marker for those that ended with a Mass Extinction:

Each mass extinction happened for different reasons and each had its own profound impact. Whole families of animals that survived for millennia suddenly disappear from the record. Ammonites, a form of shelled cephalopod that emerged during the Devonian and thrived for millions of years living through three mass extinctions did not make it through the Cretaceous. Their familiar forms abound in the fossil record and were known even back in Roman times. Graptolites, intricate colonies of animals that formed collagen structures resembling ferns dominated ancient oceans but didn’t make it through the Ordovician Extinction. Tellingly, the two mass extinctions either side of the Triassic Period were the result of rapid global warming of the kind we are seeing now as a result of human-driven emissions of Methane and CO2:

Temperature rise through global warming has been just one factor in driving previous mass extinctions. Pressure resulting from environment change was also crucial as exemplified by ocean acidification. These factors combined to create massive stress to life on earth:

there’s a dark synergy between fragmentation and global warming, just as there is between global warming and ocean acidification, and between global warming and invasive species, and between invasive species and fragmentation.

Environment pressure through fragmentation is explored in Kolbert’s book through the history of a small collection of plots of pristine Amazon rainforest preserved for science as part of the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project or BDFFP. Three hours drive outside Manaus, BDFFP has been continuously studied for decades over which it has revealed the insidious impact of fragmentation on biodiversity. A reduction in the variety of trees through patchworking led to increased stress on army ants and their struggles in turn resulted in the collapse of a whole tranche of bird life that lives off the bounty provided by the ants. There is much we still don’t know about forest ecosystems including the remarkable hidden world of mycorrhizae, the underground fungi that coexist with tree roots and through mycelium form an underground soil internet of vital importance to tree health. The true role of fungi and its interaction with other life is something we are only beginning to learn about and may yet play an outsize role in preserving the balance of nature:

try to think your way into the main part of a fungus, the mycelium, a proliferating network of tiny white threads known as hyphae. Decentralised, inquisitive, exploratory and voracious, a mycelial network ranges through soil in search of food. It tangles itself in an intimate scrawl with the roots of plants, exchanging nutrients and sugars with them; it meets with the hyphae of other networks and has mycelial sex; messages from its myriad tips are reported rapidly across the whole network by mysterious means, perhaps chemical, perhaps electrical. For food, it prefers wood, but with practice it can learn to eat novel substances, including toxic chemicals, plastics and oil.

Fragmentation is also at the heart of the story of the decline of the sumatran rhino which is now just hanging on in a few zoos its survival entirely reliant on human efforts to maintain the species through artificial insemination.

Environmental pressure ultimately drove the extinction of megafauna including the Mastadon, the Diprotodon and the Great Auk. The belief that our ancestors lived in harmony with the landscape is an enduring one but not entirely true. There is a precise correlation between the arrival of sapiens and the extinction of megaflora and megafauna across the world. This only became apparent over countless generations and wasn’t limited to just animals and flora. Neanderthals, Denisovans and all other our closest hominid relations also went extinct over the same period leading to a present-day world in which we and domesticated farm animals constitute a large chunk of life on earth. The impact our forebears had would have been even more deadly had they had the technology to operate at mass scale we do today.

Invasive species are explored in the book through the parallel stories of the devastating decline of the Panamanian Golden Frog and the Lucis bat in both cases devastated by an invasive fungal infection. Kolbert provides a memorable image of a new Pangaea where species are no longer separated because air travel has connected everywhere on earth. We’ve experienced the consequences of this ourselves over the last year with Covid spreading and mutating in China, Kent, India and Vietnam.

Ocean acidification is now increasingly understood as the “equally evil twin” of global warming playing a key role in previous extinctions. Only very recently have we begun to understand the remarkable sensitivity of ocean pH on calcifiers like the limpet and corals too. This knowledge along with the role of carbon emissions in accelerating the process has also only really become apparent very recently. Reversing ocean pH is an unfathomably complex problem.

The combination of global warming, environment fragmentation, invasive species and ocean acidification are the primary factors driving the Sixth Extinction. Anthropogenic activity has helped to accelerate their impact. We are now living in a unique time witnesses to the dawn of the Sixth Extinction. While Millenarianism has a long history in human society it has typically focussed on exogenous causes - the Rapture, the asteroid, the alien invasion. What is different with this coming extinction is that we are the root cause, the “bad news wrapped in protein” for life on earth driven. Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology hypothesises to Kolbert that we are driven by a madness gene, a “freak mutation [that] made the human insanity and exploration thing possible” since:

[Archaic humans] spread like many other mammals in the Old World. They never came to Madagascar, never to Australia. Neither did Neanderthals. It’s only fully modern humans who start this thing of venturing out on the ocean where you don’t see land. Part of that is technology, of course…. But there is also, I like to think or say, some madness there. … We are crazy in some way. What drives it?

Our central role in altering conditions on earth over the recent past is so significant that a new geological term, the Anthropocene, has been formally proposed to describe the Epoch within the Quaternary Period that started the detonation of the first nuclear bomb in 1945. Human behaviour began changing the thousands of years prior to Hiroshima and Nagasaki though. It is equally plausible to suggest the Anthropocene started forty thousand years ago when we started expanding out of Africa and leaving our mark everywhere we went. The last 250 years since the Industrial Revolution have been the completion of the work of our species taking us past the event horizon of the Sixth Extinction. We cannot bargain with what is coming, merely accommodate it.

Under a White Sky

Under a White Sky is Elizabeth Kolbert’s follow up to The Sixth Extinction. In it she explores the technologies scientists are exploring to attempt to undo what previous human technology has created. Their focus is on combatting the four new horsemen of the eco-apocalypse explored previously, namely heat, carbon, energy and food:

Heat reduction - the increasingly desperate efforts used to cool the earth.

Direct Carbon capture - extracting carbon we have pumped into the air and sea

Mass scale renewable energy - ultimately through small scale nuclear fusion

Synthetic food production - feeding the world when agriculture collapses

Kolbert provides a glimpse into the unimaginable amount of sustained multi-decadal effort we will have to put into addressing each challenge. Fifty years from now these four areas are likely to be the primary concerns for humanity and the focus of huge and desperate international effort across a damaged planet.

Heat

In terms of heat reduction without drastic global containment effort we are staring into the abyss recreating conditions in a few dozen years that no human that ever existed encountered:

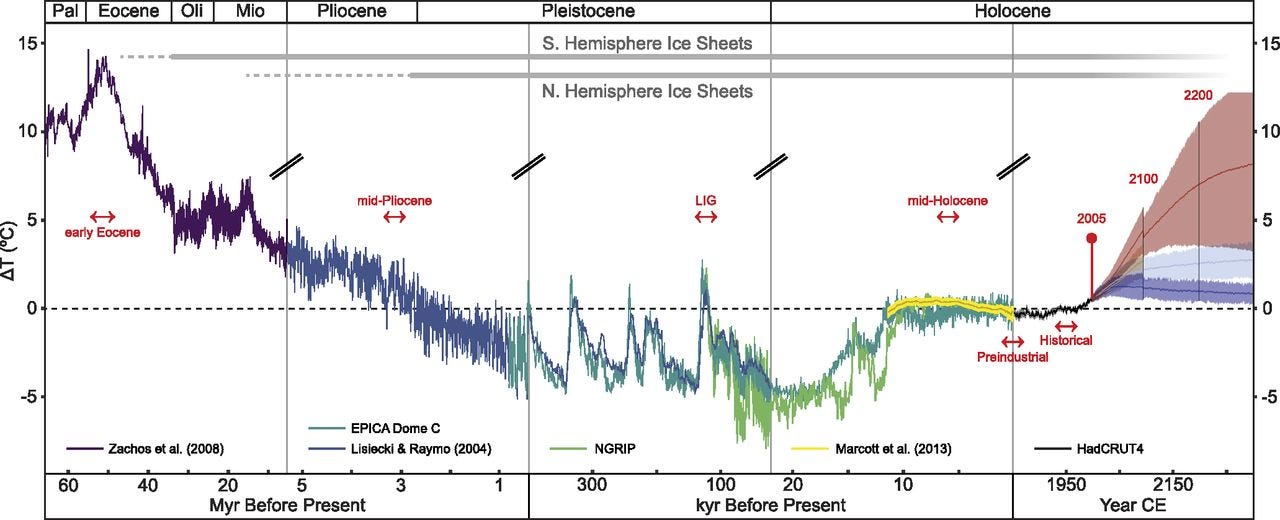

Unmitigated scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions produce climates like those of the Eocene, which suggests that we are effectively rewinding the climate clock by approximately 50 My, reversing a multimillion year cooling trend in less than two centuries.

The early effects of travelling up the curve are already becoming increasingly visible across the world notably in the US. The melting of glaciers from the Arctic and the Alps to the Antarctic has become more widely understood and reported. Indeed it may be happening faster than we thought. Phase transitions mean the melting is irreversible and the collapse of the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) could well be the defining event of the Anthropocene. Maybe the moment when it dawns on us that we have been driving massive change in geological terms without any real moment of drama we can relate to at individual human scale to date.

The key technological mechanism being touted for addressing heat rise in the short term is solar geoengineering. Work in this field involves atmospheric intervention to block heating effects through the use of sulphur or calcite released into the upper atmosphere by Stratospheric Aerosol Injection Lofters (or SAILs). The method builds on prior failed atmospheric intervention initiatives conducted by the US military such as Project Stormfury which tried to weaken cyclones through silver iodide dispersal. The problem with this sort of approach is that even if it works, it isn’t a permanent solution. The injected material eventually has to come back to earth. There are many other profound consequences of using SAILs including turning the sky white. Even so it seems inevitable it will happen over the coming decades to serve as a stopgap while we try to bring carbon capture technology up to speed. That may be the only realistic way we can stop the Arctic melting. As Dan Schrag, director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment puts it to Kolbert:

The real world of climate change is that we’re up against it. Geoengineering is not something to do lightly. The reason we’re thinking about it is because the real world has dealt us with a shitty hand.

Other outliers for dealing with heat include whitewashing as much of the built environment as we can.

Carbon

According to Klaus Lackner, the father of “negative emissions”, we need to change the paradigm when it comes to emission reduction and focus instead on removing waste:

Carbon dioxide should be regarded much the same way we look at sewage. We don’t expect people to stop producing waste. Rewarding people for going to the bathroom less would be nonsensical. At the same time, we don’t let them shit on the sidewalk. One of the reasons we’ve had such trouble addressing the carbon problem is the issue has acquired an ethical charge. To the extent that emissions are seen as bad, emitters become guilty.

The real issue when seen in this light is not emission so much as removal because the problem with CO2 is that once it gets into the atmosphere, it stays there at least on a human timescale. So from the perspective of the last 250 years since the Industrial Revolution, emissions are essentially cumulative.

There are broadly speaking three ways to extract carbon: a) direct carbon capture which involves pulling CO2 directly from the air and inject it into basalt rock, b) enhanced weathering in which crushed basalt is spread over croplands in humid parts of the world whereupon it reacts with CO2 to draw it out or alternatively olivine is crushed and thrown in the ocean in order to decalcify it, c) reforestation particularly when combined with energy production in an approach known as BECCS (“bioenergy with carbon capture and storage”).

We may know what needs to be done but the harsh reality is that the scale and cost of current carbon capture experiments are orders of magnitude out of line with where we need to be. Direct carbon capture specialists Climeworks for instance charge “$1000 a ton to turn subscribers’ emissions to stone” in a variant of a). Even if as predicted, they get the costs down to $100/ton within a decade, that would still mean removing one billion tons of CO2 would cost $100 billion. Annual global emissions today are running at around 40 billion tons of CO2 which would be $4 trillion by the same reckoning. Enhanced weathering will require mining and processing 3 billion tons of basalt for removing just one billion tons of CO2. We currently mine around 8 billion tons of coal a year. Thinking big, a trillion trees would support a reforestation program that sequestered 800 billion tons of CO2 over several decades. However:

For the trillion-tree project, something on the order of 3.5 million square miles of new forest would be needed. That’s an expanse of woods roughly the size of the United States, include Alaska. Take that much arable land out of production and millions could be pushed toward starvation.

Addressing carbon capture with “technologies that have not yet invented” is potentially the hardest of all the hard problems the Sixth Extinction will present us with. Radical solutions will be required that we can all contribute to through individual efforts. We can expect a lot more focus on wilding as evangelised in a recent book by Isabella Tree which examined the impact on a farm in West Sussex. It may become normalised in years to come to rewild as much urban space and farmland as possible.

Energy

On energy we are likely to see a massive shift from fossil fuels to solar and wind over the next decade. The rationale here is quite straightforward:

Solar and wind are inexhaustible sources of energy, unlike coal, oil and gas, and at current growth rates will push fossil fuels out of the electricity sector by the mid-2030s. By 2050 they could power the world, displacing fossil fuels entirely and producing cheap, clean energy to support new technologies such as electric vehicles and green hydrogen

The cost of solar in particular has collapsed in the 21st century to such a degree that it is viable to imagine it replacing coal. However the shift is not without consequences. Solar and wind require significantly more land to produce the same energy:

The profound consequence of decarbonisation, the switch from fossil fuels to renewables, is that it will represent the first time in human history when we shift to a less dense form of energy to sustain our culture. Then there is the daunting issue of dealing with fossil fuel debt. Rewiring America alone will require the electrification of one billion existing oil and gas-powered machines.

Fully embracing green is a huge challenge not just in terms of technology but also geopolitics. It requires a change in consciousness at a global level. It may also require us to reconsider opposition to nuclear energy albeit in the form of fusion. There are some early signs that fusion may become an option over the coming decades though possibly not at mass scale.

The switch to renewables is bound to be painful for many but there may be no alternative to switching out fossil fuels as fast as possible to avoid disaster. The technology to make it happen is well understood. The issue is one of will.

Food

Under a White Sky contains references to foods of the future from insect flour to carp patties. Alternative foods are the inevitable consequences of the pressures that agriculture ecosystems are under globally through climate change. From ocean acidification hitting shellfish to invasive species entering US waterways, global food supply is under serious threat:

"we have no evidence that the large scale agriculture we depend upon, in our billions, for survival, is possible in this new climate. Cheers"

Rising food prices and shortages in the coming years will be a key bellwether and there are clear indications of alarming deterioration. Research from One Earth suggests the situation could get a whole lot worse a couple of generations from now:

unhalted growth of greenhouse gas emissions could force nearly one-third of global food crop production and over one-third of livestock production beyond this safe space by 2081–2100.

Given that backdrop, the problem of how to feed billions of people daily is likely to become perhaps the most pressing concern for humanity presaging new famines and wars.

Staying alive

The central message provided by both Kolbert and Wallace-Wells is that humanity is on the precipice of climate chaos over the 21st century of a degree few of us can conceive today. The route by which we got here is increasingly incontestable scientifically speaking even if there are plenty of humans who don’t want to believe it. Our long-term future is circumscribed and path dependent based on our actions particularly over the past fifty years. Rather that going into space, the majority of humans will be fixing the things we broke then maybe for millennia to come. The fact that we don’t see this is because of hysteresis in the system. Like the Hollywood thriller we are in a desperate race against time but unlike the film, most of us seem entirely oblivious to what’s going on. Instead, we remain chained to a global model that prizes growth above survival. Initiatives like the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) included in US 10k corporate filings are essentially hot air:

In analyzing the disclosures of TCFD-supporting firms, ClimateBert comes to the sobering conclusion that the firms' TCFD support is mostly cheap talk and that firms cherry-pick to report primarily non-material climate risk information.

Even amongst those who acknowledge change is happening, the prevailing view is that technology will solve the problem eventually. In the West, however, technology is entirely intertwined with capitalism which is only interested in preserving itself. This has lead some to suggest the only way to save our way of life is to replace capitalism. It would be a start but technology has now transcended capital and the geopolitical norm is increasingly autocratic. We have returned to the early 70s except now unlike then “all of the world’s most powerful countries are trending toward illiberalism at the same time”:

At the precise moment we need global unity we are racing towards societal collapse isolated from each other. Bernard Lietaer in his remarkable and prophetic book, The Future of Money written at the dawn of the 21st Century outlined four scenarios for society in 2020 and it looks like we are heading straight for the heart of the most nightmarish of them:

Hell on Earth: in which the breakdown of life as we know it is followed by a highly individualistic free-for-all, resulting in an ever more obscene gulf between rich and poor

Humanity as a virus eating itself as in the haunting image of biological destiny and the Petri dish.

Is there another way? Lietaer suggested it could only happen through cooperation and thinking long term. There are some signs of hope and ingenuity. We may even be able to reverse damage by engineering specialised bacteria. We will need much more focus on thinking global to transition to a higher level of consciousness. Understand that we are part of and not apart from nature. Or as Wallace-Wells puts it, we are in the diorama not above it:

you do not live outside the scene but within it, subject to all the same horrors you can see afflicting the lives of animals.

Turning away from a growth-only paradigm and encouraging degrowth and humilty will require us all to make sacrifices. We are unlikely to ever again consume and pollute as freely as we did over the last thirty years. Doing this at a global scale will be incredibly hard, the challenge of our century. Everyone born in the next few decades will end up dealing with it and face a world that will require total transformation:

Collective human action is required to steer the Earth System away from a potential threshold and stabilize it in a habitable interglacial-like state. Such action entails stewardship of the entire Earth System—biosphere, climate, and societies—and could include decarbonization of the global economy, enhancement of biosphere carbon sinks, behavioral changes, technological innovations, new governance arrangements, and transformed social values.

Will we be able to save ourselves? The odds don’t look great given where we are and the degree of division around the planet. However Covid has provided us with a wake up call. We will need to create new forms of organisation not just new technology. Those organisational models may not necessarily be benign either. An alternative paradigm may emerge in which ascendent autocracies determine that the changes required to drive renewable energy and negative emissions technology are simply too complex to be outsourced to individuals. So they step in to control the system as a form of Climate Leviathan.

The stakes are high. Like our ill-fated traveller, beyond the event horizon we face being torn apart by the gravity differential across our own body manifest as unimaginable chaos within a single present-day GenZ lifetime. Unless we can find a way to work together one way or another as fast as possible to recover the planet, we will disappear as a mildly interesting species that never made it. Likely replaced by social rodents according to one of the scientific contributors to The Sixth Extinction. What will a Planet of the Rats make of the past? That we ended up extinct because our species would rather go to war over culture than climate? The story of that great replacement is yet to be written. If it comes to pass our main legacy will be the extraordinary drama written in the geological record studied by non-human stratigraphers of the far future:

a hundred million years from now, all that we consider to be the great works of man - the sculptures and libraries, the monuments and museums the cities and factories will be compressed into a layer of sediment not much thicker than a cigarette paper.

Perhaps nothing of our age will survive including this post. The realisation of what is happening may drive many insane while others find a new normal in which our current way of life will seem as a mirage. As Elisabeth Kolbert points out, Mass Extinctions come around once every 100m years on average. Ultimately, perhaps all one can do is just observe in silence and provide mute witness to a unique period in the history of the planet.