An AI Christmas Carol

From cloud transcription to edge computing in the living room

As another Christmas draws close, I’ve revisited a festive side project I worked on a few years ago to build an interactive voice controlled electronic Christmas tree connected to a Raspberry Pi. In November 2021, Generative AI and coding tools built with it were yet to arrive. However, GPT-3 and the fluency of its completions certainly had my attention. It seemed clear back then that software development and other creative activities would be significantly disrupted by transformer-based models. I’d written an early warning post about it called Storming the Citadel the year before:

A range of methods and tools have been developed that are capable of generating a bewildering variety of creative outputs using models constructed from trawling vast corpuses of existing work. These approaches build upon the latest advances in deep learning. Taken collectively they signpost a future where human expertise is demoted or potentially even replaced across a swathe of creative industries. A progressive hollowing out.

2025 has seen coding AI products go mainstream and they are impossible for anyone involved with software development to ignore. The Information recently reported that:

The collective revenue generated from AI coding tools like Anysphere’s Cursor and Anthropic’s Claude Code has surpassed $3.1 billion.

Most of that revenue was recorded in 2025.

This post attempts to explore this change using the Christmas tree as a prop and adopting the past future/present/future framing used by Charles Dickens in a Christmas Carol. I’ll start by reviewing the original project written four years ago explaining how it leveraged cloud services to transcribe and generate audio. I will then walk through how I bought it up to date on the latest Raspberry Pi hardware rebuilding it to work in fully offline mode without requiring cloud services. I will finish with some thoughts on where it might go in the future with edge AI integration. The evolution of the tree’s software offers a few insights on modern AI‑augmented software development, centralised versus decentralised AI and data sovereignty.

Please note, in an attempt to fully demystify the implementation, the post does get a little technical at points and includes some small code snippets. Please feel free to skip the details if you like.

And now, a video of the latest tree in action changing LEDs and “singing”!

Christmas Past

The original project was built around the 3D RGB Xmas Tree which was (and still is!) sold in kit form by PiHut. The three parts of the tree clicked together the tree plugged into the GPIO pins of a Raspberry Pi 4, the latest hardware model at that time. Here’s an image of the kit:

Once installed, I tried a few of the accompanying Python examples. I adapted one of them to create a short script called my-tree.py that cycled the LEDs through RGB colours to yield a nice phase effect. The image below is from a gif which shows what the setup looked like. The tree itself is only about 10cm high but the LEDs are super bright and can each be set to any RGB hue.

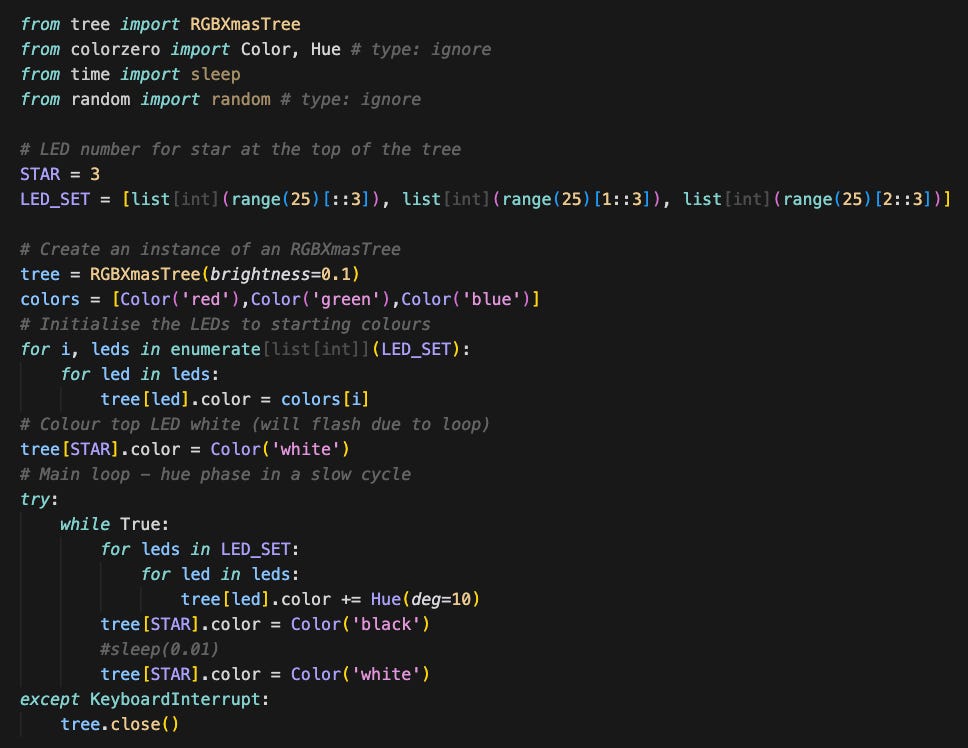

The code below is the complete my-tree.py. Non-developers should get a feel for how it works by following the comments which are the lines starting with a #:

I wanted to go further and develop a more sophisticated script which allowed you to “speak” to the tree to make it change colour and also “sing” a Christmas song. My primary motive for doing so was to learn about how to integrate voice and audio on a Raspberry Pi. I must admit I liked the idea of a Christmas tree that you could ask to play I Wish it Could be Christmas Every Day on demand in an ironic salute to the Black Mirror White Christmas episode which involves that seasonal favourite being played forever as a punishment.

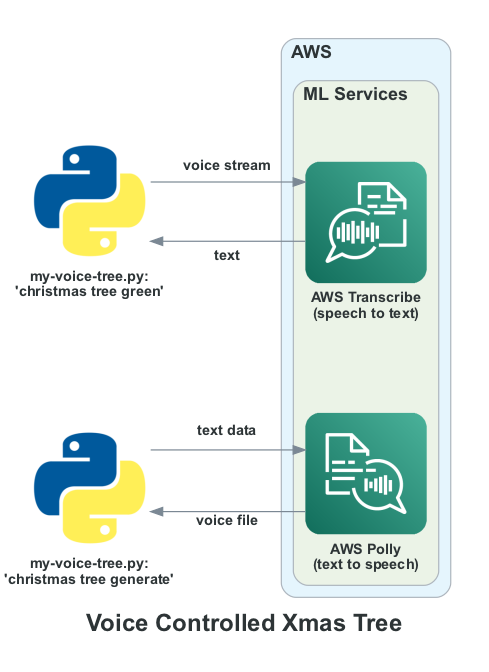

The result was a script called my-voice-tree.py in Github here which was built to interface to a ReSpeaker USB MicArray from Pimoroni as well as a cheap 3.5mm jack based speaker. It invoked two pay as you go Amazon Web Services APIs called AWS Transcribe and AWS Polly. AWS Transcribe is an ASR (automatic speech recognition) service which converts the incoming speech stream to text. The audio input is converted to a stream and sent to AWS Transcribe which returns the corresponding text. That text is parsed to extract commands which are only triggered if the wake phrase “christmas tree” is found within the text. For example uttering “christmas tree green” changes the LEDs to green.

AWS Polly is used to convert text to speech. The utterance “christmas tree generate” will result in the tree creating an audio file and responding a short time later with “hello, this is your christmas tree talking”. You can set the specific response you want to generate as a text string in the script. The relationship between the two services and script is shown in outline below:

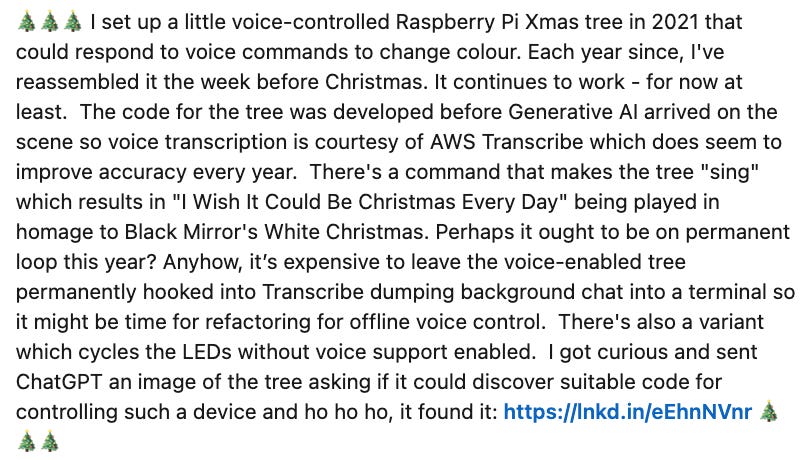

The voice controlled tree has been wheeled out every Christmas since proving popular with younger visitors in particular. Last year I posted a short note about it on LinkedIn and was surprised by the response which suggested a few others liked it too.

Christmas Present

2025 felt like a good time to revisit the script for three main reasons. First of all, the Raspberry Pi 4 I built it on is now out of date. It has been superseded by the more capable Raspberry Pi 5. Secondly, the use of AWS-based speech recognition, while noticeably better year on year in terms of speech recognition capability, had become progressively more expensive too. I ended up with bill shock last year after leaving it on for a few days continuously transcribing audio in the background. It feels like overkill for this kind of project to use a cloud service for transcription. I wanted to control the tree by voice without paying to do so. Finally, I was curious to see whether it was possible to use coding AI tools on the Raspberry Pi to support further development given their present ubiquity in the tech world. I have used several of them this year including Cursor, Codex, Claude, Antigravity and Lovable on a variety of personal and professional projects. That experience made me wonder if I could apply what I’ve learned to a legacy project. So I set myself the challenge of bringing my Christmas tree up to date using AI tools to develop the new code to integrate offline voice recognition on the Raspberry Pi 5.

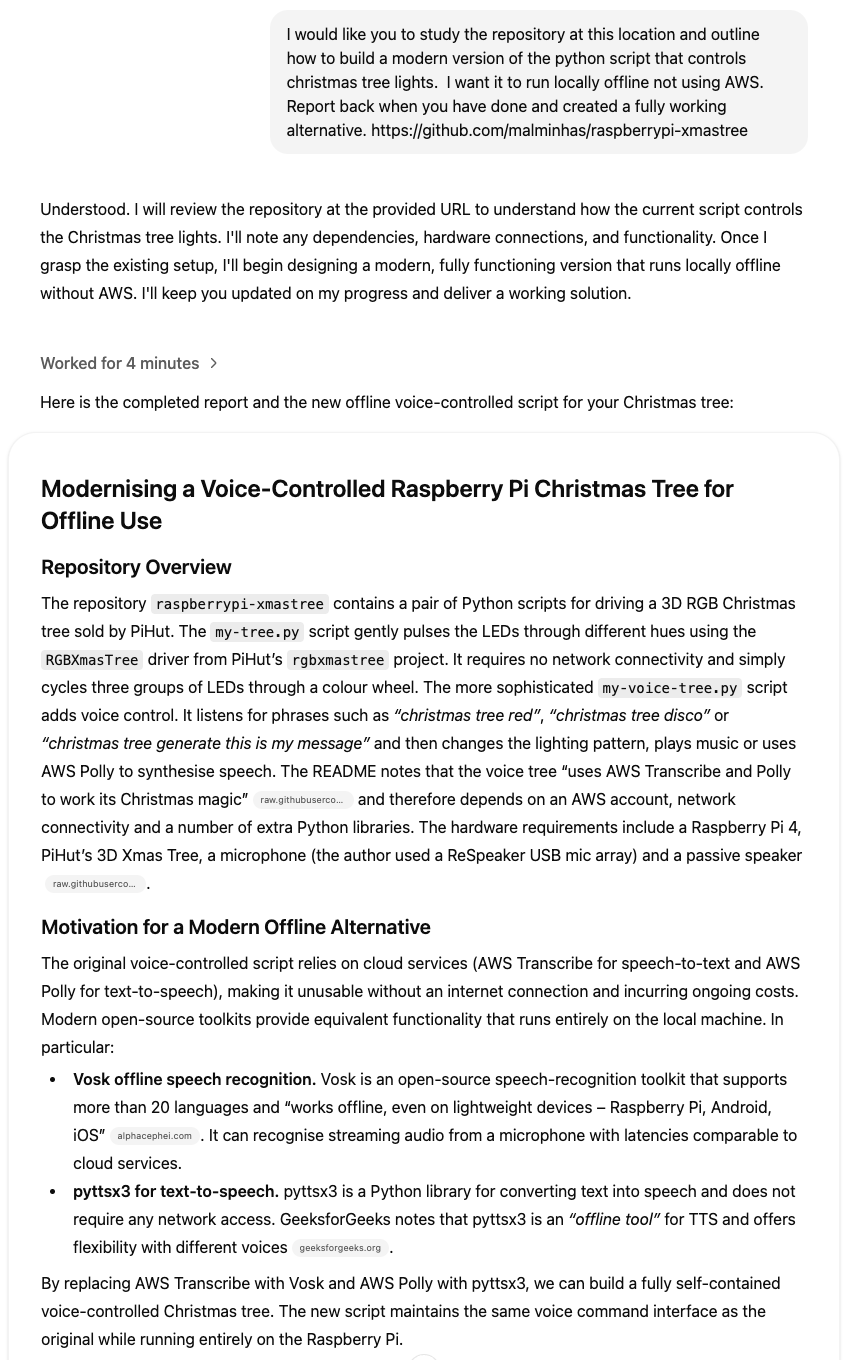

My starting point was a query to ChatGPT Deep Research pointing it at the existing open source my-voice-tree.py implementation in Github. The result was a long and impressive-looking response that included a new script called offline_voice_tree.py. ChatGPT suggested using the Vosk speech recognition toolkit for voice together with a suitably small model. It also suggested using the Python Text To Speech library pyttsx3 for generating audio. It integrated both of them into the generated script. Here are the first couple of sections of the response to give you a flavour of how ChatGPT addressed the request:

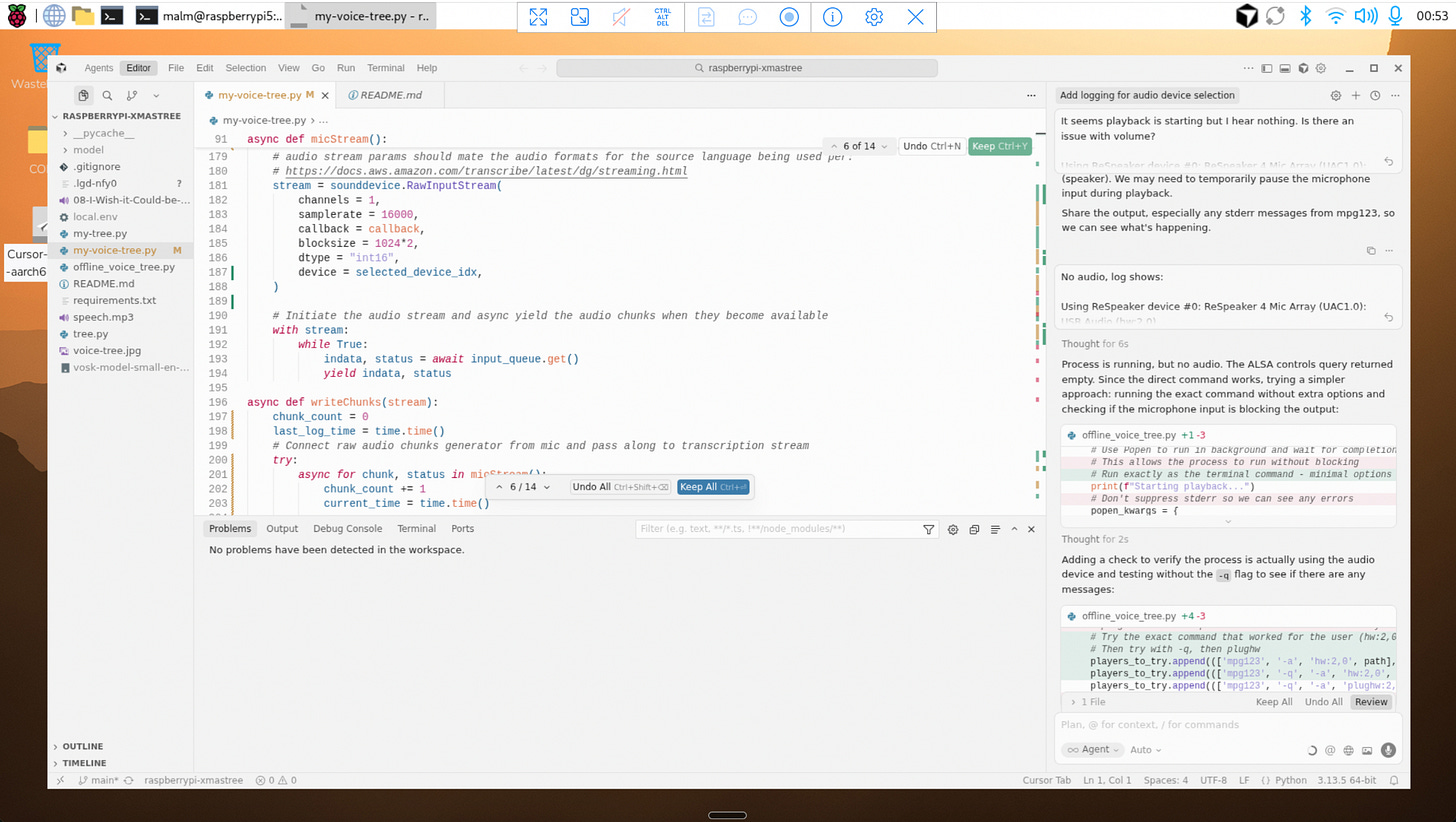

As many others have found, a fluent and comprehensive answer confidently reeled out by a large language model (LLM) is not necessarily right. I had to work through several issues in the generated source code including missing dependencies, environment variables, incorrectly named functions and finding the right directory for loading the Vosk model. If you’ve had to interface to peripherals on a Raspberry Pi, you may recognise this dance. My workflow by this point was sub-optimal. I had installed the latest version of ARM64 Raspberry Pi OS using the Pi Imager tool so I was able to use ChatGPT in the browser to generate updated versions of offline_voice_tree.py in response to my prompting. I then had to download the file, modify it to add local context and rerun it. This was acceptable for a while but I wanted a more integrated development loop. I discovered that you can download an ARM64 Linux Cursor AppImage, make it executable then run it on Raspberry Pi 5. I did so then logged in with my Cursor credentials as I would on a new laptop and found it surprisingly performant at least on the latest 8GB model hardware. I also enabled VNC support and connected to the Raspberry Pi 5 over WiFi via a client on my Macbook. This allowed me to work with it without a keyboard, mouse and monitor. Here’s a screenshot of Cursor running on the Pi:

Using Cursor and VNC allowed me to iterate faster and improve code organisation and supporting documentation. Not long afterwards, I had a version of offline_voice_tree.py working without AWS support using offline speech recognition with Vosk. A fully self-contained, offline, voice-controlled Christmas tree. This first stage of development converting voice audio input to text passed remarkably smoothly.

I took a break to understand more about Vosk. I learned that it’s an open source light‑weight speech‑to‑text engine derived from the Kaldi ASR toolkit. Each Vosk model bundles three data sources:

An acoustic model that maps audio features to phonetic units

A phonetic dictionary that spells out how each word is pronounced

A language model that assigns probabilities to word sequences

For deployment the three components are compiled into an object called a weighted finite‑state transducer (WFST) which is essentially a translator that maps inputs to outputs. A corresponding recognizer object walks the WFST in real time while it consumes the audio stream. The engine and model reside entirely on the local device, so no network round‑trip is required.

Vosk can use either small “dynamic” models or large “static” models. Small models are around 50 MB and designed for edge devices such as Raspberry Pi. They can be reconfigured at run time to limit the vocabulary. Large models are more accurate, but they precompile the entire vocabulary into a static decoding graph so require several gigabytes of RAM to run. For an embedded project like this, a small model was the only practical choice so I chose vosk-model-small-en-us-0.15 which comes in at 40MB.

Vosk also exposes an optional grammar facility to further constrain recognition. You pass an array of phrases to the recognizer constructor. The engine then decodes only those phrases, returning [unk] if the audio contains anything outside the list. According to the API documentation, using a grammar reduces latency and improves accuracy for command‑and‑control applications, but it is only supported by recognizers built on dynamic look-ahead models which are ideal for tasks where the full set of valid commands is known in advance because they allow you to preselect recognition variants with grammars. That’s exactly what Cursor built into the VoiceRecognizer class in the offline_voice_tree.py script. The result is more accurate and snappier than the older parsing method I used in my_voice_tree.py which relied on AWS Transcribe correctly transcribing the text. Both scripts employ regular expression (regex) parsing with the Python re library. Check out the VoiceRecognizer implementation here for full details.

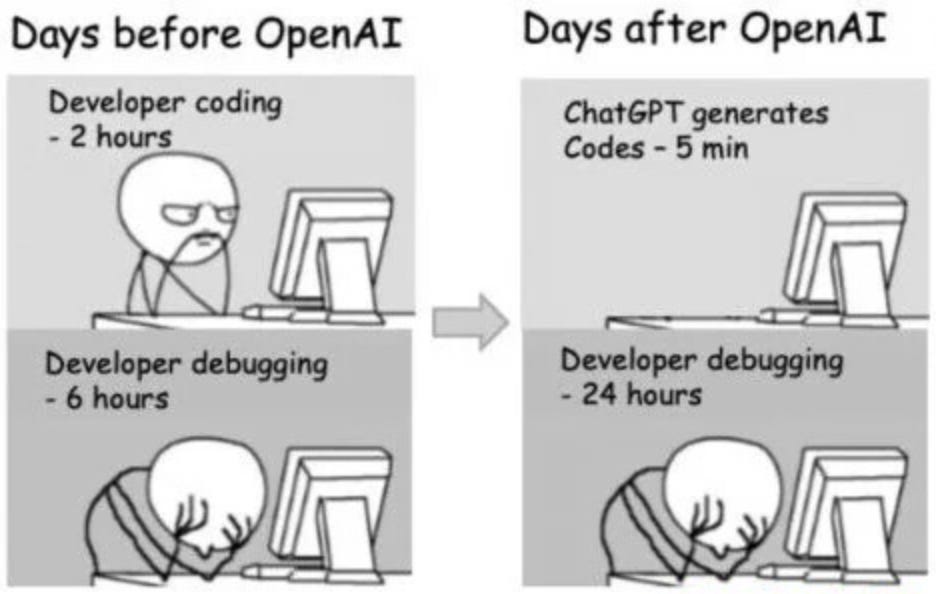

The second stage of development covered text to speech and audio playback for offline_voice_tree.py and this proved much harder. The Raspberry Pi 5 does not have an audio jack socket so I had to find an alternative path for audio playback on the jack speaker. The obvious option was to plug the speaker into the ReSpeaker mic array meaning that it served as both microphone and speaker. This may seem like a conceptually simple thing from a user perspective but it requires changes to the underlying Linux audio configuration to get sound routed to the right place. Cursor started out with the same casual confidence as before. However, this time, its initial approach didn’t work and it churned out ever more convoluted code on top of its previous efforts until it became clear a reset was necessary. After examining the diffs a while later, I reverted all the audio routing changes it had made. AI coding tools like Cursor can and frequently do get locked into logic doom loops they do not seem to be able to exit. Many developers who have used them will be grimly familiar with the phenomenon of confabulation cascade; having to periodically restore code to a last good state and reset context. Quartz recently called out it out in a post analysing an apparent decline in enthusiasm in coding AI propositions over the last quarter.

After starting afresh, I decided to figure out what was going on without using AI by refamiliarising myself with ALSA, the Advanced Linux Sound Architecture. Linux treats the ReSpeaker board as a secondary ALSA device so it is not selected as the default output. You have to probe and enumerate the available audio devices programmatically and pick the correct device index. ALSA distinguishes between raw hardware devices (hw:X,Y) and their “plug” counterparts (plughw:X,Y). The hw interface talks directly to the digital to analog converter (DAC) on the device without doing any software resampling or format conversion. For it to work, the decoded audio’s sample format, rate and channel count must already match what the hardware supports. Cursor had chosen the popular widely-available open source VideoLAN Client (VLC) media player for audio playback with hw:X,Y playback. It was failing with a “no supported sample format” error because the decoded format was incompatible with the ReSpeaker hardware. The plughw front‑end, by contrast, uses ALSA’s plug plugin to perform automatic resampling and channel conversion. Once I had configured VLC with the right parameters, playback finally worked reliably, and I could adjust the loudness via VLC’s audio_set_volume method.

Spending time with Linux audio implementation brought back distant memories of wrestling with ALSA drivers for SoundDriver cards back in the day when you often ended up fiddling with settings and recompiling drivers.

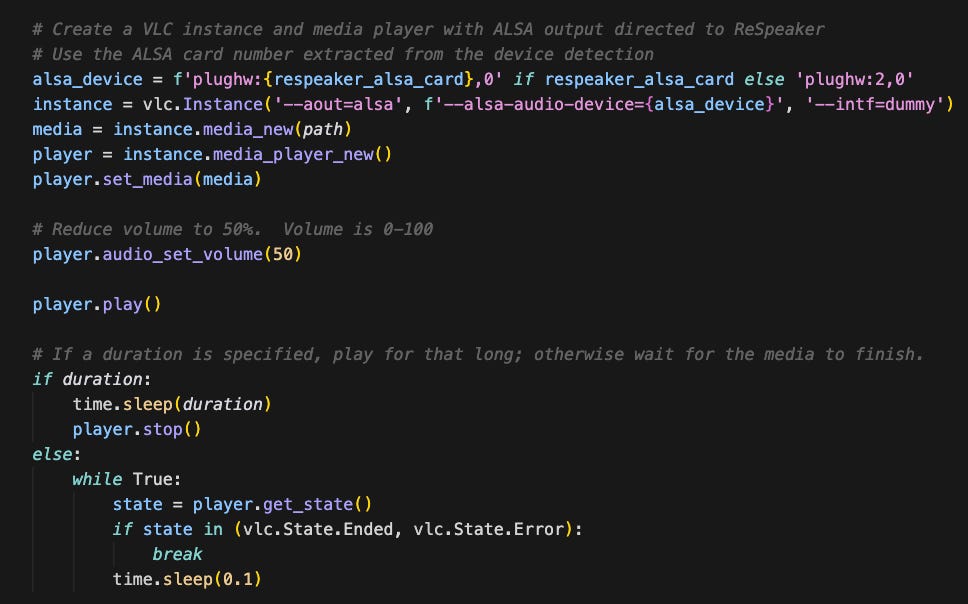

Anyhow, I eventually produced the working code shown below that plays a media file out of the speaker connected to the ReSpeaker using VLC configured with the right settings:

It wasn’t very big but this sub-20% of the file took 80% of the overall development effort. IYKYK:

I should add that later on after talking to folks who know their way around Linux that I should have used PipeWire not ALSA.

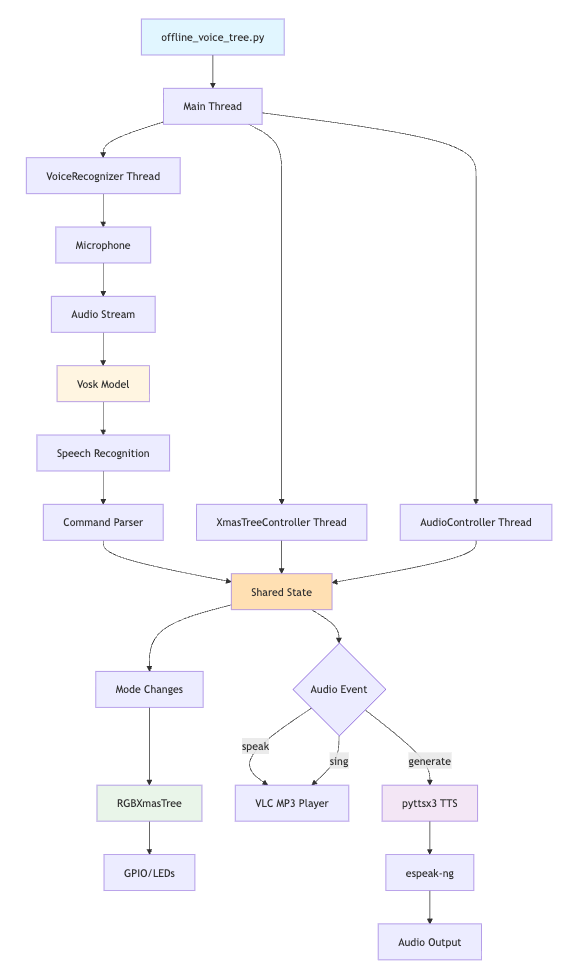

The final fully working offline_voice_tree.py script is now in Github. It supports the same set of offline commands as its online predecessor. The architecture is more maintainable and elegant as well leveraging a threading model for simultaneous voice, audio and LED control with shared memory for state. I asked Cursor to inject Mermaid system architecture diagrams into the README to render in Github. Here’s the one for offline_voice_tree.py showing how the various threads interface with other system elements:

I also used Claude to help develop comprehensive C4 compliant architecture documentation which is available here. As others are finding out this year, Claude is superb at generating good quality technical documentation.

This small side project may not be a big deal in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, it reinforces some personal observations on consumer AI technology. My experience using Cursor on a Raspberry Pi 5 for a moderately complex use case involving speech recognition and audio generation and playback shows how even embedded devices can now be supported via AI-assisted coding workflows. As little as five years ago this use case would have required cloud services and significant development. Now you can build and run a service like this in substantially less than a day on a £35 computer by leveraging a coding AI. The human plus AI co-development loop I engaged in is an example of the kind of AI-augmented engineering that many others have adopted in 2025. When used in a directed fashion in a tightly constrained context, vibe coding with AI can accelerate development.

Christmas Future

And now the ghost of Christmas Future has its turn looking out across time to show where we might be going. Appropriately, it was the scariest of all.

AI coding creates new challenges that can be hard to work through without prior developer experience. Anyone who tells you otherwise is not doing anything complicated because there are too many nuances that coding AIs are not able to work around yet. And therein lies a problem. Being able to vibe code 80-90% of an app is not that helpful if neither AI nor you is able to work out the remainder. It may be acceptable for a small side project but the level of accuracy needed for commercial applications may end up costing much more than it took to make the app “quite good”. AI skeptic Will Lockett makes the same point more bluntly in a post that references important related research from Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR):

AI gets things wrong constantly. The errors it makes are hilariously called “hallucinations”, even though that is just a blatant PR attempt to anthropomorphise the probability machine. But these errors make using AI to augment skilled tasks incredibly difficult. Ultimately, it takes a skilled worker a tremendous amount of time and effort to oversee AIs used in this way, identify their errors, and correct them. In fact, the time and cost wasted overseeing the AI are more often than not greater than that saved by the AI. This is one of the main reasons MIT found that 95% of AI pilots failed to deliver positive results and why METR found that AI coding tools actually slowed skilled coders down.

Technologist Josh Anderson is concerned about the human deskilling that results from overreliance on coding AIs and the corresponding impact it has on developer confidence around maintenance. It’s long been known that developers struggle to maintain code written by someone else. Increasingly that will mean AI as well as people. Removing the human from the development process can be dangerous in the current context when coding AIs frequently make mistakes. There’s an analogy here with self-driving cars where enthusiasts claim they are “able to drive in ideal conditions” yet they are not “at least as safe as a human” in all conditions.

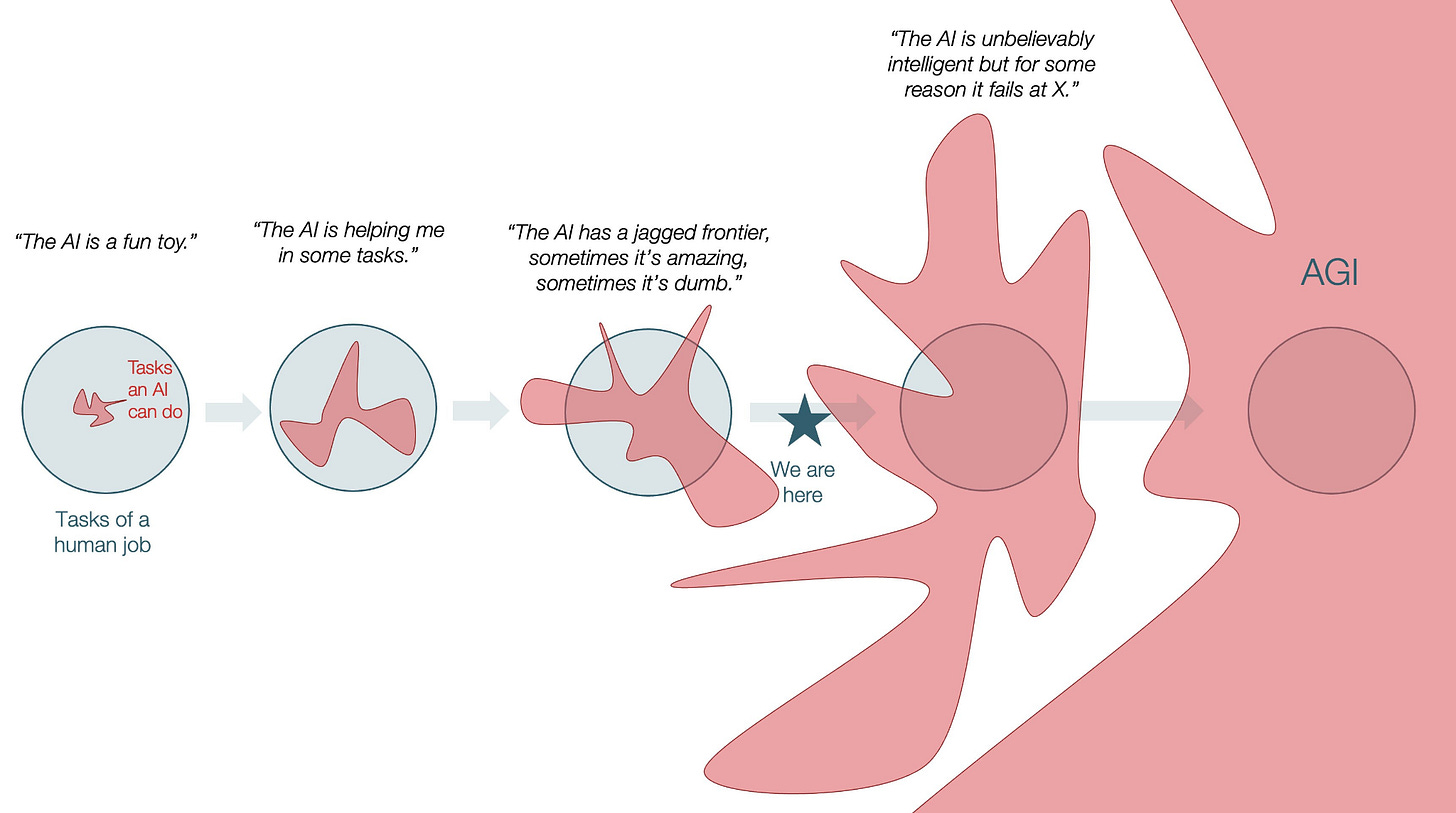

Deep learning fundamentalists, or connectionists, are convinced that AI is on a path to surpass humans at coding and everything else through scaling alone. They are sure we are en route to artificial general intelligence (AGI), namely an AI that has “the ability to understand, learn and apply knowledge across a wide range of intellectual tasks at a human level or better”. The connectionist AGI teleology supposedly emerges fully formed from today’s current ‘jagged edge’ landscape in which AI surpasses humans only in specific tasks but remains less capable in others. Here’s a view on the kinetics of the connectionist trajectory from this recent post:

I’m not convinced we will move on from the mid-point of this timeline as smoothly as the diagram suggests. At least not with LLM based architectures in their current incarnation where they don’t have a world model and don’t update their training weights to accommodate new learning. The challenges of confabulation, the split brain problem and non-deterministic results are more problematic in the real world than suggested by glowing lab baseline results. It’s a point that famed AI researcher Ilya Sutskever who helped create ChatGPT makes in an interesting but overly drawn out interview about where AI goes next:

He suggests we have reached a limit of sorts and provides this important reminder that we simply don’t understand what is really going on in the leading LLMs:

Scaling got us far, but it was never going to get us all the way. The real frontier now is understanding why these models work—not just making them bigger.

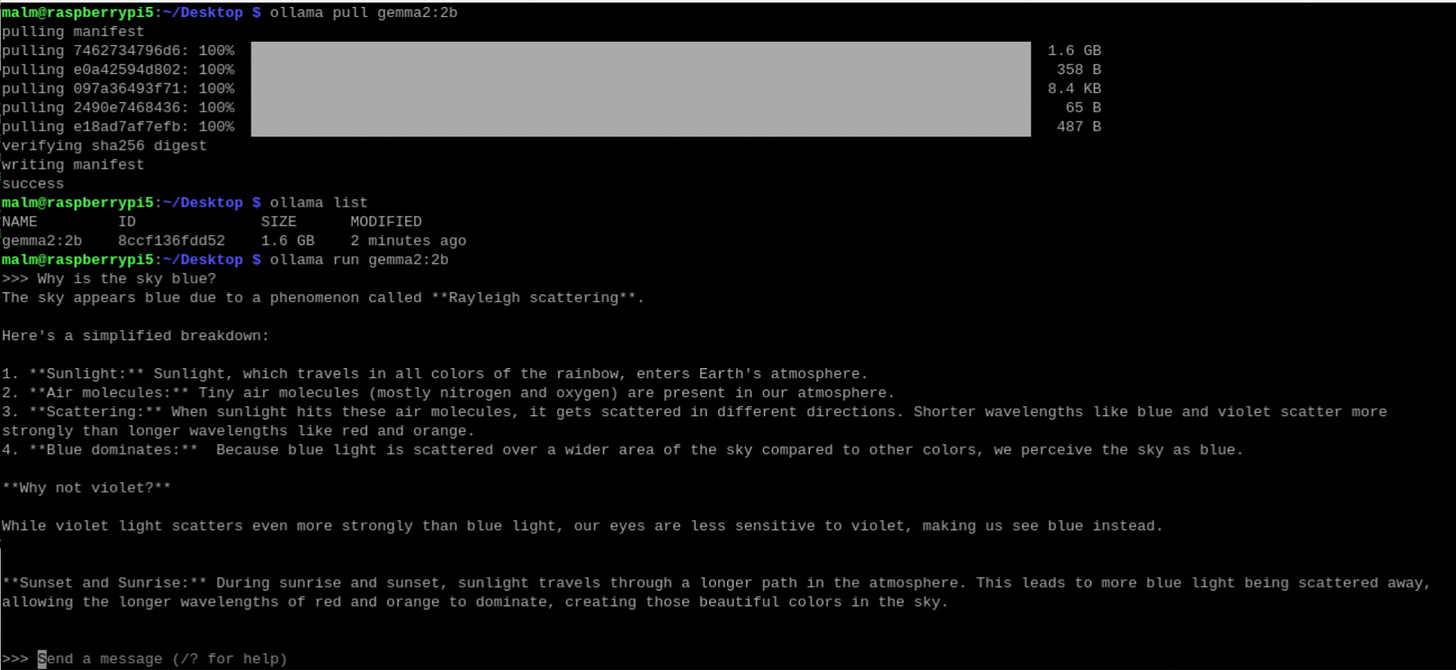

It’s worth noting that while AI was used to support its development, the offline_voice_tree.py script itself to this point has not used AI itself right now. Vosk as we have seen does not use an LLM. Its main function is to convert spoken audio into written text in a similar fashion to AWS Transcribe, not to understand context, generate human-like text, or answer complex queries like an LLM would. A next step could be to combine Vosk with a small local LLM on the device to create an interactive voice agent. The general consensus from reading around is that Google’s open weight gemma2 2b model is a good choice. It can operate at around 4 tokens/second output on a Raspberry Pi 5. Installing it via the ollama tool is straightforward. It is of course slower than using ChatGPT but its response to the question “Why is the sky blue?” shown below is entirely generated on the device without any cost being incurred other than the electricity to power it. This is a more sustainable and cost-effective use of AI than leveraging a Big AI foundation model running in a data centre likely powered by gas somewhere in the US:

It’s an example of edge computing in action and a glimpse into an alternative future quite different from the one being sold by the hyperscalers. Those outside the US may adopt a similar decentralised approach for their use case and leverage open weight models, frequently Chinese, running on hardware they control which is entirely offline if required. The history of computing is replete with progressive waves of diffusion from the centre to the edges. From the cathedral to the bazaar. Why should AI be any different? For a lot of inference-based use cases, access to a centralised model is overkill. Performance, however, is an issue. The main problem with a local LLM on the Raspberry Pi is latency. It takes too long to round trip for interactive voice scenarios where a snappy response is critical. A cloud-hosted LLM is necessary but does it have to be US based and powered by fossil fuels? Can we use a more ethically and environmentally conscious choice? I recently learned through the GreenWebFoundation of GreenPT, an EU technology company that provides a sustainable and privacy-friendly AI platform accessible via an API. GreenPT emphasise environmental responsibility and data protection and run a variety of open weight models in their data centre in the Netherlands including DeepSeek and Qwen3.

In an attempt to conjure a view of this future, I added initial support for LLM integration to offline_voice_tree.py. The latest version allows the user integrate either with the gemma2 2b model using an ollama module or with GreenPT via their pay as you go API using a greenpt module. The latter will be very much faster than ollama on the Pi so I have set it as the defualt. I used GreenPT’s hosted version of gemma-3-27b-it to support a couple of new commands:

joke- tells a family-friendly festive jokeflatter- generates a ridiculously effusive panegyric for dictator-curious users

I also upgraded the speech output capability as it was sounding just too tinny with longer text. It’s now possible to switch between pyttsx3 and piper as underlying offline text to speech engines on the Raspberry Pi before invoking vlc for a more natural voice. Here is a video of joke in action using piper for text to speech with its aru voice which sounds like a GenZ kid. I adjusted the prompt to make the gag more political and topical. The first result suggests an admirable emerging social awareness. Perhaps Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is closer than I imagined?

I’ve been separately working my way through PiHut’s fantastic Codemas Advent calendar this month which includes various sensor surprises your can integrate with a Raspberry Pi Pico using Python.

It’s a relatively small step from using voice to tell jokes to using it to interface with the real world at home. Nick Bostrom in his influential book Superintelligence terms the transition from oracle to genie the “treacherous turn”. He sees it as the key step to becoming the equivalent of the wizard of fairy tales. In his framing the next stage is becoming an omnipotent sovereign or ruler in charge. For Bostrom the concern is not AGI which he sees as a short blip, but ASI, Artificial Super Intelligence. This is a level of intelligence far beyond our own which we will not be able to control and it will be attained through recursive self-improvement when the AI can improve itself without human involvement. This dynamic helps explain the intensity of hyperscaler investment in centralised AI. In that context, it feels important to exercise great caution over who has access to, and control of, your home environment and personal data in that scenario particularly if they don’t share your values.

The shape of things to come often arrives in the form of a curiosity, a toy that contains within it the imperceptible tremors of unimaginable futures. For now the tree is up and running on a Raspberry Pi 5 changing LEDs, singing and telling jokes with much improved audio command detection and text to speech and that’s enough magic for this Christmas.